by Ken Sharratt

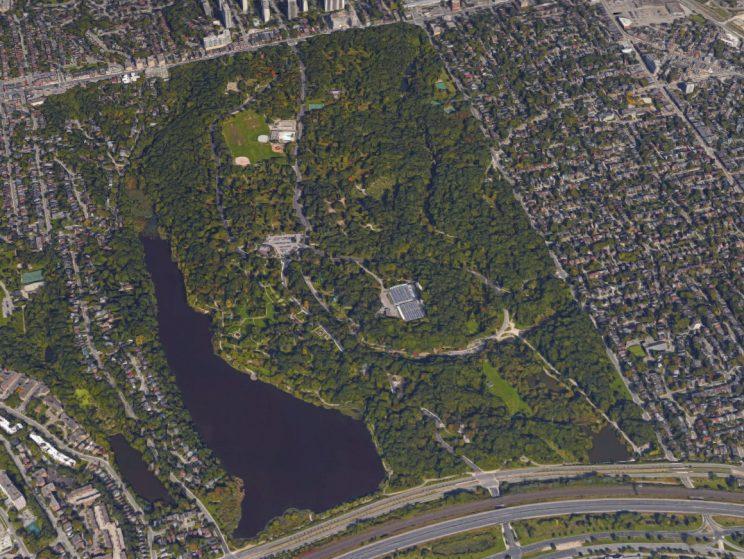

High Park shares a common geological history with the rest of the waterfront areas of the Toronto Region. Canadian Shield bedrock is situated about 400 metres below the surface. Sitting on top of this are a number of layers formed at various times over geological history starting with limestone formed when the area was an ancient sea. Over the past 135,000 years, through a series of glacial advances and retreats, additional levels were laid down. The most recent glaciation, which began its withdrawal down the St. Lawrence River valley about 12,500 years ago, set the stage for the creation of Lake Iroquois, a large lake covering the present Lake Ontario basin. The lake was formed from melt water from the glaciers. Because ice blocked the present St. Lawrence River, the melt water from Lake Iroquois flowed south to the Hudson River in what is now upper New York State.

Lake Iroquois was much deeper than present day Lake Ontario. High Park would have been under sixty metres of water. During this period, large deposits of sand and other fine material were laid down under water over the present shoreline and High Park. Soil analysis has shown that the soils are sandy loams with a topsoil layer ranging from 0 to 14.5 cm in depth. Yellow to bright orange sands are found below this topsoil. The soils have a low organic and nutrient content.

About 12,200 years ago, the St. Lawrence Valley (where Kingston is today) suddenly opened, and the water from Lake Iroquois quickly drained. The situation was like a tilted bathtub with a drain that became unplugged. Two factors exacerbated the extent of the drainage. First, the land in the St. Lawrence area was depressed by the weight of the glaciers, compared to current levels, making drainage more rapid. Second, the ocean was about 100 metres below current levels, since much sea water was tied up in glaciers. This lower level meant that more water could leave the basin.

The resulting new lake shoreline was about 8 kilometres south of High Park. Rivers and streams that previously drained into Lake Iroquois now immediately began to cut into the soft sandy sediments that were formally lake bottom.

In High Park, water flowing through Spring Creek and Wendigo Creek cut deep steep-sided ravines. Spring Creek entered the current park at what is now Parkside Avenue and Bloor Street, then meandered south. Spring Creek had a number of tributaries that can be clearly seen in today's ravines, such as where the adventure playground and the zoo are located. A number of smaller ravines fed into these and the Creek.

These ravines and streams accounted for 50% of the park area. They contained forest vegetation. (HTO page 287). The land left between the ravines, termed tablelands, was sandy and relatively warm. This land supported more southerly plant types including Black Oak woodlands and open areas or savannahs with a prairie understory. (oak savannahs are considered a provincially rare community type). The valley bottoms and slopes were swampy and cooler and supported more northerly species such as cedar, red oak and other such plants.

As time passed, further geological changes affected High Park. The land at the eastern end of Lake Ontario began to rise after the ice had retreated and the weight of the ice was removed. This rebounding of the land reduced the outflow from the lake and caused lake levels to rise. Over the time, lake levels continued rising and the shoreline moved to its current location. When this happened, the valleys of the streams that had cut into the soft sediments were flooded. The wave action along the present=day beaches and resulting sediment movement eventually blocked the mouth of the Creeks, trapping ponds behind them. This is the origin of Grenadier Pond on Wendigo Creek and the marshy area and Duck Ponds at the lower part of Spring Creek. Grenadier Pond is now the City of Toronto's only remaining lakeshore marsh and occupies most of the western side of the park. (Varga, 1989)

Sources

- Ed Freeman Formed and Shaped by Water: Toronto’s early landscape Nick Eyles Ravines, lagoons, cliffs and spits: the ups and downs of Lake Ontario in HTO edited by Wayne Reeves and Christine Palassion, Coach House, Toronto 2008.

- A Botanical Inventory and Evaluation of the High Park Woodlands, S. Varga, 1989.

See also

- Natural History of Toronto's High Park

- Laurentian River

- Quaternary Geology of Toronto and Surrounding Area, Southern Ontario map

- TORONTO'S GEOLOGY (including history, biota and High Park), Frank Remiz. PDF (600 Kb)

- Water levels in Lake Ontario 4230–2000 years B.P.: evidence from Grenadier Pond, Toronto, Canada; Mccarthy and McAndrews, 1988