A Walk Back in Time

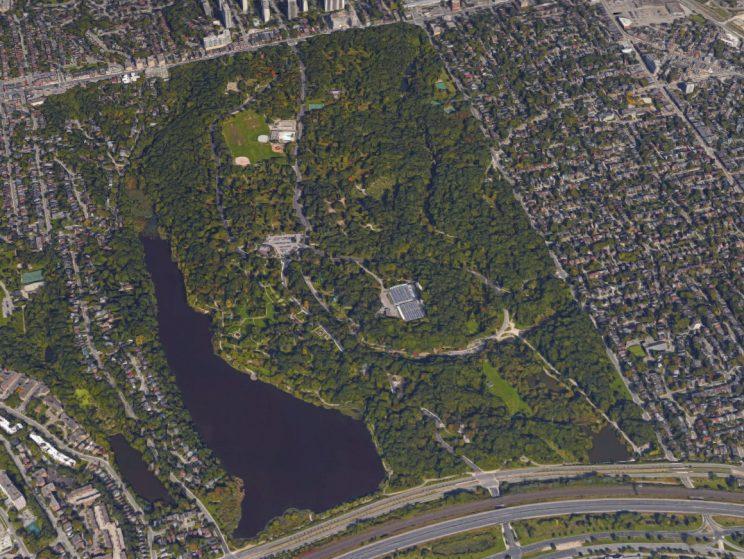

Steep-sided ravines are a major feature of High Park’s topography. This varied topography dates back to the post-glacial period when the larger Lake Iroquois (the precursor of Lake Ontario) was eventually released into the St. Lawrence Valley and then shrank in size, exposing soft sandy sediments. Two major streams – now known as Spring Creek and Wendigo Creek – as well as their tributaries cut through the sandy sediments, forming the ravines we see today. These ravines support a variety of habitats, and each different habitat supports a different mix of plants and shrubs.

The Ridout Property

Long before John Howard bought his 67 hectare property, the long established Ridout family owned 69 hectares of land on what is now the east of the park extending from Lakeshore Road to Bloor Street. While maintaining their homes on Front Street in the city, the family built their farm on the land now occupied by the Howard Park Tennis Club and the lawn-bowling clubhouse (also used by the High Park Nature Centre). Ridout Street, on the east side of Parkside Drive just south of Bloor, was named in their memory. The city purchased 172 acres to the east of the Howard property from the Ridout family in 1876.

Historical Contours

Just north of the Ridout property that now forms the eastern portion of High Park was the swamp at today's Keele and Bloor Street intersection. The contours of the saucer-shaped depression where the swamp once sat can still be seen today.

In 1875, John Howard drew a map of High Park with three main tributary valleys connecting to the Spring Creek Ravine. The Jamie Bell Adventure Playground (The Castle) lies in one valley and the High Park Zoo in another valley. The ravine that lies behind [the former site of] the Nature Centre has been filled at Parkside but remains the most natural remaining example of a tributary valley in High Park.

The Eastern Ravine

Imagine a time before Parkside Drive existed. In contrast with the prairies and dry oak woodlands surrounding it, this small ravine just west of Parkside Drive contains many moist and wet habitats. Wet meadows and marshes flourish at the bottom of the ravine. Deep and narrow, it traps the cooler air. It is coolest on the east-facing slopes because it is in shade for most of the afternoon. Just underneath the sandy soil of the park's uplands is a layer of clay that forces water to travel sideways - creating a supply of water where it seeps out along the lower slopes of the ravine. Due to the constant presence of water and the cooler temperatures, the forest and marshes are rich in plant life and alive with creatures.

This ravine is home to six different plant communities (a group of specific plants and trees that live together for different reasons). The ravine's dominant plant community, the Red Oak-Red Maple Deciduous Forest, is found no where else in the park. Two other plant communities, the Red-osier Dogwood Thicket Swamp and the Bluejoint Meadow Marsh, are found in only one other place in High Park. The coolest areas have more boreal affinities, with Eastern Hemlock and understorey plants associated with more northerly conditions.

Sources

- High Park Nature Centre, A Quick Guide to Walking in the Ravine brochure, April 27, 2008.

See also

- University of Toronto’s Faculty of Forestry. Toronto Ravine Revitalization Study. Featured under our Research section.

- City of Toronto. Ravine Strategy.

- City of Toronto. Toronto Municipal Code, Chapter 658: Ravine and Natural Feature Protection.

- City of Toronto. Toronto Ravine and Natural Feature Protection brochure.

- The Star article. How Toronto’s ravines have become critically ill — and how they can be saved. By Francine Kopun, November 2018.

- The Guardian article. 'There's no major city like it': Toronto's unique ravine system under threat. December, 2018.