by Kathleen Keefe

IIn 1836, with intentions to run a sheep farm, John and Jemima Howard bought 165 rural acres stretching from Lakeshore Road up to Bloor Street. On this land they built a country home known as Colborne Lodge. The Howards’ property became the basis of High Park when they deeded most of it to the city in 1873.

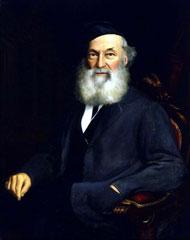

Professional Work and Art

The couple immigrated to Canada from England in 1832. John accepted an appointment as drawing master at Upper Canada College and kept his affiliation for 23 years while also establishing himself as Toronto’s first professional architect and one of its first official surveyors. He laid out Toronto’s harbour, waterfront and islands, and engineered Toronto’s first sewers, bridges, streets and sidewalks. John Howard worked like crazy for 20 years, often exhausting himself. Jemima played a key role in John’s successful practice by preparing copies of specifications for his projects.

In addition to his legacy of professional work, John’s amateur watercolour paintings provide a valuable record of 19th century Toronto life. For example, one shows cows being herded down King St. past the jail, the fire hall, the courthouse and St. James Anglican Church. Jemima, also an amateur painter, focused on romantic themes.

Colborne Lodge

As an architect, John may best be remembered for his charming Regency Picturesque style houses, such as the Howards’ own High Park home, Colborne Lodge. John designed their country home to complement the natural surroundings and named it after Sir John Colborne who helped him get his professional start in Toronto. Perched on a hill overlooking Humber Bay, the view inspired the estate’s name: High Park.

Colborne Lodge began as just three rooms in 1837 and was used in different ways as it grew. The Howards lived there full–time for the first few years, then moved back to the city and used it more as a country retreat. Initially, John and Jemima slept in what later became the library. The eventual dining room was originally the kitchen, but in the summer, cooking was done under an overhang off the back of the house. Originally, there was a cellar accessed through a trap door in the dining room. The servants’ room was located where the bathroom is now. In the 1850s, a full basement was added to accommodate the servants’ quarters and a winter kitchen.

In time, the servants hired would come to include a family with children. The husband took care of the animals, the wife cooked and cleaned and the children did chores. Special windows and window wells were designed by John to let light into their basement quarters. The greenhouse, added in the 1860s, was the last addition to the house. By the time it was finished, Colborne Lodge had grown from just three rooms to 22!

John Howard read Scientific American magazine and eagerly adopted new ideas and inventions. The icehouse north of the coach house indicates they had an icebox. The dining room fireplace mantel was made of a new composite stone material. The “marble” fireplace in the drawing room was painted by John Howard to look like marble. The best examples of his enthusiasm for modern devices are in the Howards' bathroom (see below).

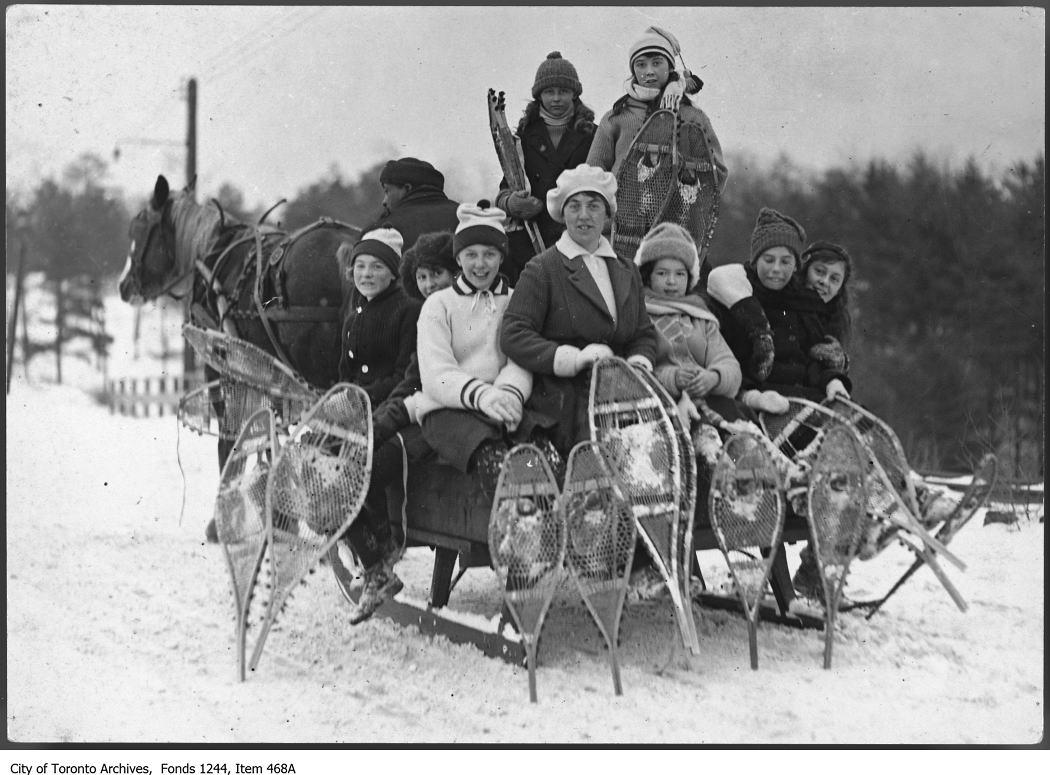

Life at High Park

The Howards kept much of the land in its natural wooded state but planted orchards and gardens around their home. They also rented out land south of the present day Grenadier Restaurant to tenant farmers. The current park office was designed by John Howard and served as a home for the farmers. Alfalfa and wheat fields grew on the slope that extends up from the present-day floral maple leaf.

John Howard allowed the soldiers and officers from Fort York to fish at Grenadier Pond and to gather greenery for Christmas decorations. He and Jemima entertained the gentry for carriage rides, picnics, boating, fishing and walking. The couple also formed close ties with two of their live-in servant families, the Duffs and the Hills. The Howards hosted charity picnics, such as the Oddfellows Picnic for the poor, as it was their intention that all Torontonians use the park.

While John and Jemima did not have any children together, John had three children with his long-time mistress, Mary Williams. Howard’s papers reveal an ongoing relationship with his clandestine family. He provided money and ideas for Christmas celebrations, drawings and designs by the children can be found in one of Howard’s sketchbooks and he provided for them in his will. Having a mistress then was not uncommon, but it would have been kept discreet. Nevertheless, in such a small town, Jemima may have known about the affair. At one time, John himself (originally known as John Corby) claimed to be the illegitimate son of a man with the surname of Howard.

When John retired in 1855, the Howards made High Park their full-time residence and John spent his time working on the grounds of their estate. Both John and Jemima were avid gardeners. Current garden restoration at Colborne Lodge is based on John’s journals and diaries.

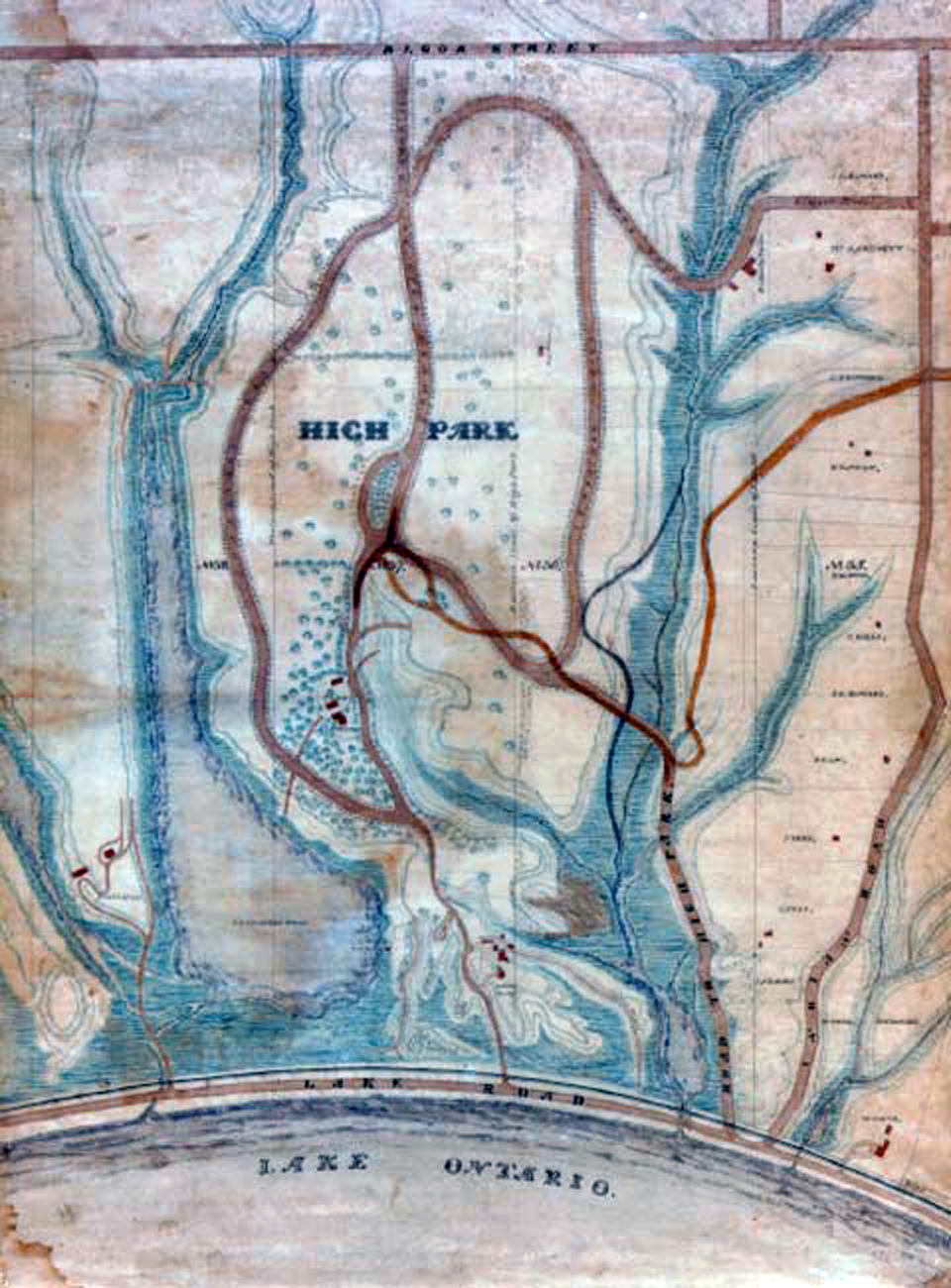

A Park for the People

In 1873, the Globe and Mail ran an article describing how the benefits of parks could solve social problems. John Howard designed public spaces thoughtfully with this in mind. He was aware of the pro-development ideas Frederick Olmsted applied to Central Park. While Olmsted wanted to create a groomed park from scratch in Manhattan, Howard really wanted to keep High Park as natural as possible. He was not a fan of fountains or arbours in his park. John Howard’s 1870s plan for High Park can be viewed in the Colborne Lodge library. The current layout of the park with the ring road around the tableland and the north and south entrances is fairly close to his original vision.

The City added the 170-acre Ridout property to the park in 1876 and held a design competition for architects and surveyors. Howard deemed their plans too intrusive and rejected them all in favour of keeping the park in a more natural state. At his own request, John Howard was appointed Forest Ranger of High Park in 1878. Back in the 1870s and 1880s, Dufferin St. was the western limit of the city and the roads beyond were rough. Still, enough picnickers were willing to make the trip. Howard cleared brush and designed roads and drains. Wanting visitors to enjoy nature without the presence of “drinking booths or alehouses”, he stipulated no alcohol in the park, and High Park remains the only “dry” area in Toronto. By the time of John Howard’s death in 1890, streetcars came within walking distance of the park.

The Howards’ Final Years

As per an agreement with the City, the Howards lived out their days in High Park at Colborne Lodge. After years of suffering, Jemima died of cancer in 1877. She was the first woman in Toronto to be diagnosed with breast cancer, and a pathologist in England confirmed the diagnosis when he received John Howard’s sketch of a ruptured lesion. Jemima was put on heavy mind-altering doses of opiate painkillers. According to John’s journal, she began spilling things, breaking things and running away to places where he had a hard time finding her. With an aim of obtaining the best possible care for her, he approached the Provincial Lunatic Asylum (a building he had designed with state-of-the-art facilities). However, the doctor in charge advised against such a solution. So, reportedly for safety reasons, John put her in the guest room, installed a door with no inside handle, put bars on her windows and hired two live-in nurses. When she passed, John seemed to sincerely grieve her loss.

There are some who believe Jemima haunts the house. In 1969, a police officer patrolling the park observed a figure in a second-floor bedroom window but found no one when he investigated. When visiting Colborne Lodge, some people have reported getting a prickly sensation, an uneasy feeling or seeing something out of the corner of an eye.

John died at Colborne Lodge in 1890, 13 years after Jemima. Upon his death, his remaining 45 acres and Colborne Lodge became city property and officially part of High Park. (The City added another 71 acres in 1930, bringing the total size to about 400 acres, or 161 hectares.) John and Jemima are buried near Colborne Lodge in the ten-tonne tomb he designed. Boulders on the bottom provided assurance against grave robbers and represent a Scottish cairn in honour of Jemima’s heritage. The marble Maltese cross topping the monument was brought from Vermont, and this Masonic symbol represents John’s membership in the order. The fence around the monument dates back to the 1700s. It once formed part of the fence encircling St. Paul’s churchyard and was designed by Sir Christopher Wren. The ship transporting the fence from London England sank in the St. Lawrence River and Howard hired divers to salvage the fence from the wreck (see The Story of a Fence).

Colborne Lodge is now a fully restored living history museum open to visitors. Because of the Howards’ early foresight and generosity in the 1800s, today more than a million annual visitors are able to enjoy High Park right in the middle of Canada’s largest city. The Howards would be glad to know that much of the 400-acre park is maintained in its natural state as John Howard requested. They’d also be pleased that it is reached easily by public transit and bicycle.