by Kathleen Keefe

Here is the startling truth: On a High Park trail there are more creatures below the ground’s surface than above it. Signs of abundant animal life surround us, but an extraordinary multitude of creatures lives beneath us.

At least 90% of all organisms on earth spend some part of their life in the soil. This includes High Park’s community of soil decomposers made up of microfauna, mesofauna and megafauna, as well as mammals, reptiles and amphibians.

Some creatures that spend time underground: Microfauna; Mesofauna; Macrofauna such as Ants, Yellowjackets, Bumblebees, Great Golden Digger Wasp, Cicada-killer Wasp, Velvet Ant Wasp, Solitary Bees and other invertebrates; mammals such as Meadow Voles, Groundhogs and Chipmunks, Foxes and Coyotes; and Snakes, Toads and Turtles.

Ants

Beneath us, ants live in colonies connected by tunnels that resemble streets of a city. At the center is the queen who can live more than 25 years and lay up to 200 million eggs! The eggs become larvae, the larvae become pupae and the pupae turn into the adult ant forms we see above ground.

Each ant is born to perform one of four specific jobs for the colony: Nurses care for the eggs, larvae and pupae. Foragers provide food. Excavators build tunnels and chambers and remove the soil. Waste managers remove dead ants and uneaten food to special waste chambers.

Yellowjackets

Like ants, many species of wasps and bees are “social” and create very organized nests below ground. Others are “solitary”, establishing underground nests for just their own brood.

One example of social wasps is the familiar yellowjacket. If you come upon many insects emerging in flight, one after another, from a single hole in the ground, you may have found the entrance to a yellowjacket nest.

After spending winter in a protected brush or leaf pile, a fertilized yellowjacket queen surfaces in spring to find a safe spot for her colony. A preferred nest site is an abandoned rodent tunnel. To begin the underground colony, she lays several eggs that hatch and mature into adult workers. These workers perform all the duties of nest expansion including food foraging, colony defense, tending to the queen, caring for the new larvae, and nest building. The workers construct the underground nest by bringing in bits of tree, chewing it into pulp, and layering it to form a comb.

The underground colony grows quickly, sometimes numbering in the thousands by fall when new males and replacement queens are raised. After the new generation mates, the males die and the queens overwinter. What’s left of the season’s underground nest perishes with the cold temperatures.

Bumblebees

Bumblebees also prefer to nest underground in abandoned rodent tunnels with dominant queens ruling their social colonies. Their nests run in much the same way as yellowjacket colonies, although with less organization and on a much smaller scale, with just 50 to 500 individuals.

In spring the queen emerges from hibernation and urgently collects nectar for the enormous task ahead of her. When she locates an appropriate site, she burrows down into the ground. Then, using wax flakes shed from her own body, she forms a little cup and fills it with the nectar she’s collected. She makes another cup and tightly packs it with pollen she’s collected. Atop this, she lays the first generation of eggs. The queen feeds from her nectar pot and sits on her brood cell shivering her flight muscles to generate heat. Once the little white C-shaped larvae hatch, she must leave the nest often enough to gather pollen for them and nectar for herself. It’s a risky business – if the nest temperature drops below 25°C while she’s out foraging instead of heating the nest, the larvae will die. At this critical stage many queens and nests are lost.

If all goes well, the larvae will then spin cocoons, and a few weeks later the first brood of bumble bee daughters emerges to take over the work of caring for the nest, the queen and the next brood. On very hot days, the workers fan their wings to keep the nest temperature below 32°C.

The season’s final brood of eggs includes replacement queens and drones. The queen larvae are fed three times more pollen than other larvae. As adults the new queens gorge themselves on nectar, both in the nest and outside, trying to store enough energy to survive the winter. The drones and queens will mate with those of other colonies and then the queens will find a protected place to overwinter. All other members of the underground colony perish.

Great Golden Digger Wasp

One example of solitary wasp is the Great Golden Digger Wasp. As their name suggests, these wasps excel at digging. The female is built to excavate tunnels with jaws that loosen the soil, legs and body that roll it into a ball and front legs that fling it away. She constructs a long vertical tunnel about 1.5 cm wide and 15 cm deep with two or three side chambers. She provisions the chambers with insects she has paralyzed with her venom, typically katydids, crickets and grasshoppers. She drags a paralyzed insect into each side chamber, lays an egg on it and seals the entrance. After provisioning the chambers, she backfills the tunnel and never returns. She will dig as many as eleven nesting tunnels and provision them this way.

When the eggs hatch, the larvae consume the paralyzed but still-living insect. After a few weeks, they spin silky cocoons in which to pass the winter. They pupate in the spring and emerge as adults in early summer. After mating, the females bulk up on nectar and search for sandy soil in a sunny spot to start tunneling for the next generation.

Cicada-killer Wasp

When the female of this imposing species is on the lookout for a good nest site, she seeks light, well-drained, sandy soil in full sun near trees that host cicadas. She digs a 1.5 cm wide tunnel down through the soil to a depth of 30 to 40 cm and then tunnels horizontally for a metre or more. To excavate, she uses her jaws to remove soil and her spiny back legs to push it out. She removes enough soil to fill a shoebox! Along the tunnel, she builds a dozen or more egg-shaped side chambers, furnishing each with one to three cicadas she has paralyzed with her venom. She then lays an egg on each cicada and seals the chamber with soil.

This keeps her busy for several weeks from July’s end to the beginning of September. By day, she stays in the tunnel and by night, she flies around preying on cicadas. The grub-like wasp larvae hatch in two or three days and for the next ten days, they feed on the paralyzed cicadas mom provided. If the nest survives, each larva spins a silken case in the fall, and prepares to overwinter. Threats to the nest include marauding skunks that devour both the cicadas and the wasp larvae.

Velvet Ant Wasp

Another enemy of ground-nesting wasps and bees is the velvet ant. This parasitic wasp measures just under 2 cm. The females are covered in orange and velvet-like hair. Being wingless they can be mistaken for ants. They don’t make their own nests, but rather seek out underground brood cells of other wasps and insects. The involuntary hosts include solitary bees, flies, some moths, beetles and cockroaches.

The opportunistic velvet ant wasp lays her own eggs on the host’s pupae. The eggs quickly hatch into white legless grubs that consume the defenseless host and pass through several larval stages before pupating. The velvet ant wasp is relatively safe in the usurped underground cavity, but not so when it is running around topside trying to locate the underground nests.

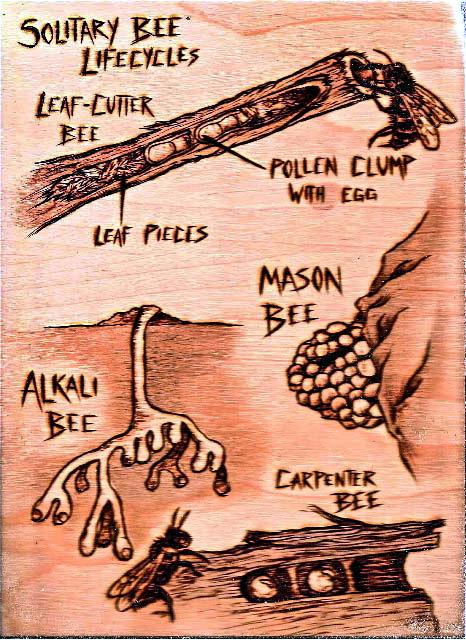

Solitary Bees

More than 350 native solitary bee species were recorded as residents of the GTA in 2011, and about 70% of them nest in the ground. Nearly all of these important pollinators produce just a single generation a year. High Park’s sandy soil is just what these ground-nesting bees prefer because it’s easy to excavate. Instead of one large communal nest, the females make separate tunnels next to each other, often digging them in a bank exposed by a dip in the land. They choose southeast facing sites that will be warmed up by the early morning sun.

Most solitary bees excavate and complete one brood cell before beginning the next. Into the completed brood cell, the female puts a ball of pollen and lays an egg on top. To prevent water-logging in heavy rain, ground-nesting bees commonly waterproof the brood cell with their glandular secretions. For eleven months of the year, the eggs develop into insects underground. Then, in a perfectly coordinated convention orchestrated by nature, the adult bees emerge from the ground precisely at the bloom time of the flower they pollinate.

An example of solitary bees often seen in High Park in April and May is the stingless cellophane bee (AKA: tickle bee) that comes out in sync with the flowering of maple, redbud, willow and chokecherry trees. In April or May, an east-facing sandy hill in the oak savannah may be alive with thousands of bees, each emerging from individual nests dug side by side. Most solitary bees are harmless, not having stingers large enough to puncture human skin. So, tickle bees come by their innocent nickname honestly.

Other Invertebrates

Moths: Even some moths pupate underground. When the larva is fully grown it looks for a good spot to pupate. Once this is located, the larva digs down with modified knobby forelegs and forms a chamber where it will pupate. When the adult moth is ready to emerge, the pupa wriggles to the ground’s surface and splits open to release the moth.

Dog-day Cicadas: Dog-day cicadas, so named because one hears them in the dog days of summer, reach an impressive length of up to 33 mm with wingspans of up to 82 mm. Females lay eggs under tree bark. The hatched nymphs drop to the ground and burrow under with their forelegs to reach tree roots. They feed on the root sap, growing and molting over several years underground. Nymphs emerge from the soil and, using their claws, they climb a tree trunk. By midsummer the nymph shell splits and an adult cicada emerges.

Centipedes and Millipedes: Preying on the spiders, ants, beetles and slugs are the centipedes. There are many different centipede species but all seek the moist dark conditions offered underground. These quick voracious hunters pounce on their victims and inject poison with their fanglike front pincers. Eyeless soil centipedes move wormlike towards their underground prey, pushing forward with the front end and then pulling the back end along. As they pursue insect larvae, worms and other centipedes, their movement through the soil improves its quality by aerating it and allowing water, minerals and nutrients to reach plant roots. Millipedes need the same kind of dark moist environment to survive, but they have more of a janitorial role in soil management, feeding on rotting and decaying plant material and breaking it down for use by other organisms. Both centipedes and millipedes overwinter in the soil and lay their eggs in the soil. Hatchlings molt several times on their way to adulthood and then live five years or more.

June Beetle: AKA May beetle or June bug, these red-brown beetles appear on warm spring evenings, flying around erratically and bumping into things. Each female feeds, mates and then buries 50 to 100 small pearl-like eggs in the soil before she dies. Within 30 days, the eggs hatch and for the next three years, the larvae stay underground feeding on plant roots. Over that time, the white C-shaped larvae grow to be 3 cm long and then pupate and emerge as adults in late summer. They bury themselves underground again for the winter and emerge in spring to feed, mate, lay eggs and die less than a year after they first emerged as adults.

Spiders: Not all spiders use webs to catch their prey. Certain species of wolf spider dig tunnels and wait inside for dinner to fall in. They construct relatively vertical tunnels, some as deep as 170 cm! They loosen the soil with their very hard front fangs and use their heavy forelegs to aid in the excavation. Once a pellet of earth has been extracted and compacted, it is carried up to the top and flung away by powerful forelegs with such force that it lands 6 to 50 cm from the tunnel entrance. Some of these spiders will opt instead to combine the pellet with spider silk and vegetation and build a rim around the mouth of the tunnel. On average, the tunneling spider removes over 900 little balls of earth to create its burrow. To prevent the tunnel from collapsing, it may line the tunnel entrance with silk. The burrowing wolf spider spends most of its life underground in its tunnel, but if the burrow is invaded by ants, the spider hastily flees its home.

Meadow Voles

Meadow voles dig short shallow tunnels, eating the grass and roots as they go. They cut numerous trails through grass and soil, creating several entrances. Connected to the tunnels are burrows dug just 10 cm deep where they make nests of grass, leaves and stems. A number of adult voles, along with their young, share a burrow system.

Groundhogs

Groundhogs spend most of their time underground in tunnels and burrows. Aided by their sturdy claws and muscular bodies, groundhogs are such accomplished diggers that they are sometimes thought of as underground architects. The burrow is a system of tunnels with one main entrance and up to four additional entrances. The burrows are all located below the frost line. A large mound of fresh earth conspicuously marks the main entrance. The entrance is perfectly constructed to prevent flooding of the burrow.

The groundhog starts by tunneling downward for more than a meter and then tunnels upward for a short distance. Then safely below the frost line at a depth of about a metre, it tunnels horizontally for five to eight metres. A few side tunnels leading to other areas are constructed off the main tunnel. The different dens are used for hibernating, sleeping, nesting and raising young. One of the areas is used by the groundhogs for the sole purpose of depositing their bodily waste. Once this area is full, its tunnel entrance is sealed and a new latrine area is excavated.

Groundhogs truly hibernate, staying underground throughout the winter in a coma-like state from October to February. The females will stay underground until March when they emerge and mate. The kits are born in the den a month later, staying underground nursing and growing until the mother cautiously leads them outside for the first time at six weeks. The groundhog’s nose, eyes and ears are all on the top of its head so it barely needs to raise its head above the ground’s surface to make a quick check for danger. Near the burrow’s entrance, the mother teaches her kits how to eat vegetation. At the first sign of danger, she whistles and instantly they disappear back down into the burrow.

Eastern Chipmunk

The eastern chipmunk spends most of its life living alone underground in a vast and well-appointed burrow system. Its burrow is key to the chipmunk’s success in life because it serves as a safe place for sleeping, eating, hiding, raising young and surviving winter. At a metre deep, the borrow is below the frost line and can reach up to nine metres in length! To prevent flooding, chipmunks dig narrow drainage tunnels at the bottom of the burrow. They leave small inconspicuous camouflaged openings at several burrow entrances. Fresh dirt is carefully removed from the entrances so the burrows are less evident to predators. The chipmunk’s tiny size means it has many predators to run from. Not surprisingly, it stays fairly close to home, ready to dash back into one of the burrow entrances at the first sign of danger.

All the chipmunk’s tunnels lead to the main nesting chamber, which is lined with insulating leaves, thistledown and vegetation. The nesting chamber is kept immaculately clean and is used for raising young and for sleeping. Even in summer and fall when they are at their busiest, chipmunks sleep about 15 hours a day underground in their burrows. Chipmunks stay below ground in their burrows throughout the winter from October into spring. What they do underground for those months is actually a mystery. Some researchers believe they eat all their stored food and then go into a deep sleep. Some believe they enter the deep sleep at once and wake up occasionally to snack on the stored food. The burrow is fully stocked with seeds and nuts stored in side pockets along the tunnels. A chipmunk can stockpile as many as 165 acorns in a single day! Layers of seeds and nuts have been found beneath the insulation of the nesting chamber, presumably for easy access by the busy mother with a litter of helpless pups.

Red Fox

A female red fox prepares a den as soon as she has mated. She may dig her own den or take over and modify an abandoned den. She also prepares extra dens in case the first den is disturbed and she has to move. Her den has several entrances that lead to a tunnel running as long as 22 metres. She creates several chambers off the main tunnel that are used for storing food and raising young. Two pairs of red foxes might share the same den system. The kits stay in the den, nursing for four or five weeks while the male brings food to his mate. The parents and sometimes older offspring work together caring for the kits underground in the den. Foxes use a den only temporarily while raising young and only occasionally do they take shelter in an abandoned den at other times.

Coyote

Likewise, the only time coyotes go underground is for the pupping and whelping season in spring. In April, when birthing time is near, the female looks for an existing den, perhaps abandoned by a skunk, raccoon, fox or groundhog. If she finds a suitable den, she might enlarge it and add an additional entrance. Failing that, she will excavate her own burrow, often into the face of a bank. Males do not enter the den but they bring food to the den for the female. After two weeks, both parents supplement the pups’ milk diet by regurgitating food for them at the den. When the pups are fully weaned, the coyotes leave the den and stay above ground. The female may return to the same den the following year to have pups, or she may prepare a new site.

Eastern Garter Snake

A snake’s body temperature depends on the temperature of its surroundings. The eastern garter snakes in High Park seek shelter with other snakes in underground chambers known as hibernacula where they can share what little body heat they have and avoid freezing and dehydration. Finding the right site is no easy task. In order to satisfy their requirements for temperature and humidity, the snakes must account for solar orientation, depth, distance from the frost line and water table, ground material and ground cover. They often take over abandoned rodent burrows that meet their specific requirements and have several different exits. The snakes return in great numbers year after year, following the trails left by other snakes that have already traveled to the den.

American Toad

The American toad also hibernates underground below the frost line. To look at a toad, you would not think that it could dig a deep enough den. However, it is equipped with hardened knobs on its hind feet that enable it to dig far down. It will spend the entire winter alone in its deep hole and emerge only when the soil temperature warms up in the spring.

Turtles

In spring, turtle mothers dig holes in the ground to lay their eggs. After the female deposits the eggs, she fills the hole back in with earth and then leaves them to develop and hatch underground. Snapping turtles hatch in the fall and dig their way out of the nest. If they successfully run the risky gauntlet of predator-filled terrain to the water, they bury themselves in the muddy bottom for winter. Midland painted turtles also hatch in the fall but they stay underground in their nests until spring. Their blood contains an antifreeze-like chemical and the little hatchlings stack themselves underground in the hole in a heat-retaining formation. In this way, they are able to pass the entire winter underground in their nests.